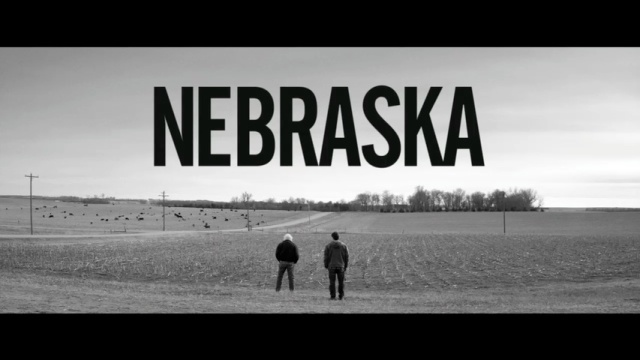

Alexander Payne’s Nebraska is a love-letter to his native state, to a dying way of life, to characters both flawed and uncomfortably familiar, and to a landscape so desolate as to send shivers down your spine. It is all these things but also, I think, Nebraska is a film about the craft of making quiet, tender movies; about the visual weave of character, and landscape done in black and white. Payne does not beautify either his character or the land, but he casts a light–literally–of dignified resignation on his material, turning the drear of living in these desolate places into scenes of profound portraiture and painterly depth.

Nebraska is nothing if not all these things rendered with such skill and restraint that you can easily be fooled by the narrative’s simplicity and the re-working of an old American genre: a father and son on the road from Billings, Montana, to Lincoln, Nebraska. But what a father-son team these two characters (played by Bruce Dern and Will Forte) make! Payne sets them against the background of equally memorable secondary characters whose collective presence is as powerful as the chorus of a Greek tragedy although the film’s surface is full of comedic energy and quirky dialogue. The gallery of these character is crowded but not stifling, yet it is Dern and Forte, more so I would say Forte, who take hold of our attention and keep it sustained for two long hours as the two men chase a false dream. Well, at least the father is chasing the false dream; the son’s role is more complex.

Above and beyond the comedic energy, the stunning photography of the Mid West plains, the masterful script, what is most striking in this film, and in others by Payne, is the way Payne toys with sentimentality, with material that could easily slip into maudlin fluff, into the kind of optimism that brings in a lot of money, sells a lot of pop corn, and reproduces the illusions–large and mundane–which so much of Hollywood and mass culture perpetuates. Payne’s material is always the folly of human beings, the false hopes and soaring dreams which sustain but also destroy, which can be profound but also carry a lot of shallow humor. He has been called one of our most humanistic film-makers for this reason, I think. But he refuses, often, both the easy answer as well as the complex explanation, finding a path between these two extremes.

Nebraska looks simple but you ask, Is it simplicity or is it that Payne has willfully avoided complicating things so much that these flesh-and-bone characters lose their humanity but also their core attitudes? Is it that Payne sees his characters through the explicit, comedic lens or is it that what is left unsaid, what is evaded and avoided lurks just below the surface. After all, what is evasion if not the other side of what is seen, to which it is inextricably attached? To make it all explicit is to fall into the mesh of sentimentality and melodrama, to hold the material hostage.

Like the road itself, the film passes, refuses to hold on to too much, allows for a weak narrative (perhaps) but honors the human beings on the road. “Intimacy passes,” Richard Rodriguez has written. Nebraska is a most intimate film because it avoids so much, steers clear of so much. What a great film!~~